Hagio Moto, The Heart of Thomas

May. 29th, 2013 01:37 pmThis is the first of what hopefully will be a series of conversations about narratives of assorted kinds. In each, we’ll attempt to give enough background about the events of the narrative to enable people unfamiliar with it to follow the discussion, but we’re aiming for critical readings rather than reviews. There will be many spoilers.

We are following the Western convention for Western names (personal name, then family name) and the Japanese convention for Japanese names (family name, then personal name).

The Heart of Thomas (トーマの心臓) by Hagio Moto (萩尾 望都) was published in 1974. It is one of the first works of shounen ai (a genre now often called "boys' love" or BL) and is considered a manga classic. The first English edition was translated by Matt Thorn and published by Fantagraphics in 2013.

Trigger warnings: There are some descriptions of physical and emotional abuse and implied sexual assault.

—![]() coffeeandink (Mely) and

coffeeandink (Mely) and ![]() oyceter (Oyce)

oyceter (Oyce)

Mely: So, should we start off with a plot recap? In Hagio Moto's Heart of Thomas, a German schoolboy named Thomas commits suicide, leaving a note for the crush who rejected him, a boy named Juli. Juli's guilt and resentment become inescapable when Erich, a new student who looks uncannily like Thomas, enrolls in the school. Erich himself contends not only with his own response to Juli, but also with feeling abandoned by his mother, who sent him to boarding school after she remarried. A third major character, Juli's friend and roommate Oskar, also faces questions of identity and abandonment: after his mother's death, Oskar's father (the man who raised him) dropped him off at boarding school, and hasn't been heard from since. Oskar knows that the school's headmaster is his biological father, but neither of them has admitted this to the other.

Oyce: I've seen the basic plot description--namely, Thomas’ suicide, the arrival of lookalike Erich, and Juli’s reactions to them--multiple times in reference to the manga, but the manga really doesn't go where I expected with it. I thought it would be a much more traditional romance focusing on Juli and Erich, complete with Erich feeling as though Juli were only attracted to him due to his resemblance to Thomas.

Mely: Where do you think that impression came from?

Oyce: I think some of it is influenced by my knowing that this is a seminal work in creating the BL genre, so I thought it would be more explicitly BL. Instead, not only does Juli remain single, the conflict is less about Juli’s feelings about romance and more about dealing with trauma and expectations and healing.

It's much more psychological than I had been expecting, even knowing that everyone praises Heart of Thomas for that. I was pleasantly surprised by the focus on Juli’s struggles with accepting love and how Hagio uses both Thomas and Erich’s attraction to Juli to focus the story on that.

Mely: I, too, feel like the book isn't exactly a romance. It's more a story about recovery from abuse that uses romance as a vehicle, or that talks about romance insofar as Juli's romantic feelings are affected by his history of abuse, rather than a romance featuring an abuse survivor. Although I had some issues with the way the abuse was treated.

It's clear from pretty early on that Juli has been abused in some way or gone through some extremely traumatic incident involving physical violence. Ultimately, we learn that he was assaulted by a group of upperclassmen led by a student named Siegfried.

It is definitely sexualized violence, although I'm not sure if we're supposed to read it as a literal sexual assault? The significant pages are focused much more on the emotions than on the physical acts, and the acts that we know about specifically are Juli being burned with a cigarette and being whipped with a teacher's cane; we also see his bloodied face pressed against the floor. I read it as having a very strong sexual subtext. So much of the story is about experiencing or evading sexuality.

Oyce: Yes. I definitely read it as rape.

Mely: In the end, what we get is a Juli who blames himself for being abused -- he is seduced by Siegfried into danger, he is abused by Siegfried, he remembers himself as having felt some emotional and/or physical attraction to Siegfried. The final version of the story, and the one we are probably intended to take as truthful, is that Juli sensed both that Siegfried was dangerous and was sexually attracted to him, and followed him into the clubhouse willingly -- where he was assaulted/raped. And Juli blames himself for his own assault. "I was drawn to him," Juli says. "I … knew what kind of upperclassman he was. One part of me whispered that I should stay away from him. There is a good seed and a bad seed in my heart. The good was drawn to Thomas. The bad was drawn to him. I said that my wings were torn off … but the moment I accepted Siegried's invitation … I had thrown them away myself."

And -- that is where the story ultimately leaves us. Juli is able to heal because he acknowledges his own "complicity" in the assault. This allows him to acknowledge his attraction to/love for Thomas. And as a result of this acknowlegement, he ... decides to leave school and become a priest. He renounces all sexual desire and, perhaps even more importantly, all emotional attachment to his current set of friends, leaving them for a new isolation.

As you can probably tell from the quote-marks around "complicity," I think this is a terrible story, and that it says a lot more about cultural attitudes about abuse and rape than it does about actual healing.

Oyce: Oh, that's interesting. I didn’t quite read it that way. I came away with Juli finally accepting that being raped or abused didn't make him unworthy of Thomas' or Erich's love. I felt the conflict for Juli wasn't so much admitting that he felt attracted to Erich or Thomas or even Siegfried, but more that he wasn't even worthy of human affection.

Much of this is related to the prevalence of Christian themes and imagery throughout the manga: Juli refers to himself as an angel with its wings torn off, and the shame he feels about his scars from the cigarette burns inflicted by Siegfried match the shame in his words when he talks about the scars from the loss of his wings. After Oskar inadvertently sees his cigarette burns, Juli thinks, “This scar. This... scar! This devil’s deed! This seal of blood! This curse!” He then continues: “I sing the hymns and speak of God. Yet I’ve lost my angel’s wings [...] I trust no one. I love no one. So no one need love me. No one need believe in me.”

But when Erich sees Juli in the library, he sees a figure with shimmering wings, and later, Juli wonders if reaching out to Erich will let him get his angel’s wings back. He’s connecting his own experiences of being raped and abused, of not being able to love or be loved, with a sort of fall from Heaven, so it doesn’t surprise me that when he finally allows himself to love and be loved, he makes the jump into the church’s arms.

Mely: Yes, that makes sense. But I question the movement from accepting that he's worth affection to moving away from all personal affection. Definitely the emotions we get from the scene are peaceful, serene, even a kind of joyous dedication. But this is expressed by removing himself from the friends whose affection he is finally able to acknowledge.

Oyce: I feel like it's a very shoujo reading of abuse. There's a lot in there about guilt and self-hatred and turning anger in on yourself instead of on your abuser that I find very symptomatic of shoujo. And probably also the USian romance genre, actually.

Mely: Oh, yes. Oh god, Fruits Basket.

Oyce: I liked the ending of Thomas because it wasn't a typical romance, though I’m torn about the aspect of choosing reclusiveness. It reminds me a lot of a short story in Yoshinaga Fumi's All My Darling Daughters, where I was completely blindsided by one character coming to the revelation that she couldn't do personal romance because it meant loving one person more than loving other people, which was antithetical to her desire to love all people equally. And thereby, she chose to cloister herself away as a nun. I’m now wondering how often this shows up in other shoujo manga.

Mely: Juli in Thomas and the daughter in the Yoshinaga story did make me think of characters in Genji renouncing desire and becoming Buddhist monks or nuns; obviously, this kind of renunciation has a long history in Japanese culture. So Hagio and her readers have a Buddhist cultural context for finding happiness in the rejection of personal connection, not just the Christian one I initially read because of the setting.

Oyce: I find the insertion of the spiritual into the story and the use of human romance to parallel or symbolize divine love interesting. Siegfried believes that religion is evil and faith is a “fragile convenience,” and when he is abusing Juli, he coerces Juli to say that Siegfried is above Juli’s god. Even though Siegfried is obviously a sexual threat, the biggest threat he poses is a spiritual or philosophical one. The sexual threat is a physical expression of his nihilistic philosophy.

Mely: So, in that sense, Juli becoming a priest is replacing Siegfried-God-nihilism with God-human-love.

Oyce: Yes, and Siegfried's negative view of mankind and mankind's inability to truly love with the idea of an all-loving God who also loves Juli. I don't know how much of this is influenced by my own Christian cultural upbringing. But then again, it's explicitly Christian in the text.

Mely: I tend to read the background mostly as the exotic Occident rather than an attempt to engage with Europe/Christianity, but at the same time there are obviously things about Europe/Christianity -- or the Japanese projections of them -- that are meaningful philosophically in the story.

Oyce: Yes, exactly. I do feel the view of an all-loving God is something that Hagio is taking from Christianity and playing with. The idea of forgiveness for everything is a notion that she seems to like.

There almost seems to be a thread of how human love can't quite encompass the depth and desire of humans to be loved. Thomas is elevated to nearly saint status in the end, when Juli accepts his love because Thomas has already forgiven him of all sin.

And Erich is content with his love for Juli not when it's consummated in any sense, but when it frees Juli.

Mely: Can we relate this to an all-loving parent? That's very Freudian, but I feel like the psychology here is very Freudian. There's this kind of inevitable separation or tragedy created by the child's expectation of being the center of the parent's world -- the parent being the psychological center of the child's universe -- and the parent's inability to fulfill that role.

Oyce: Yes, very much so. And also reversed when Erich cannot be a Thomas-substitute for Thomas' mother.

Mely: Yes, exactly -- there is this devouring need between parents and children which founders on absence, whether it's the absence of death or the withdrawal of interest. Which is especially clear in Erich's relationship with his mother, Marie.

Oyce: I am sure you are unsurprised to hear I was a bit disturbed by the Erich-Marie relationship. It's very much represented as a romance in ways, particularly how Erich is threatened by the presence of Marie's boyfriends and has his breakdown when he sees Marie and his tutor kissing.

It's just, ugh. The Erich-Marie thing is so Oedipal!

Mely: Oh, Marie. So many issues. Perhaps you should not be sharing your suicidal tendencies with your young child, Marie! Perhaps this is an inappropriate intimacy and burden for a prepubescent child!

Oyce: She's eventually redeemed in Erich's eyes when Erich finds out that she wanted him in the end, but there is so much displacement of desire and trying to center her entire world on her young child!

Mely: Marie actually reads as bipolar to me? The sort of manic frenzied focus on Erich and then the frenzied depths of despair.

Oyce: I hadn't thought of it in exactly that way, but that reading doesn't surprise me at all.

Mely: But at the same time I don't think the intent is a realistic psychological portrait -- since we really do not get any realistic depth for Marie -- but as a weirdly infantile and emotional narcissism, which only loves Erich insofar as she sees him as part of herself. She is just so -- childish. And it is a huge problem for me that we only see women and girls in this story from the outside, and that they are such stereotypes.

Oyce: Yes, very much so. And it's in context of historical shoujo also featuring stories of preteen girls in fairly limited roles. I find it especially interesting that Hagio said she tried writing November Gymnasium (a shorter version of Thomas using the same character) with school girls but changed the characters to school boys because “it came out sort of giggly.”

Mely: Yes. We have the three mothers and Juli's saintly and sickly little sister. (I can't even remember her name, I think of her as Beth from Little Women.)

Oyce: Amusingly, she is actually named Elisabeth!

Mely: Cheers for my partial recollection and/or the influence of 19th century American literature! Anyway, there's Thomas' mother (who I tend to think comes off the best, possibly because her actions are horrible but are clearly coming from the midst of new mourning), Erich's mother, Oskar's mother.

Oyce: And Thomas' mother isn't quite as emotionally dependent as Marie, but the little we see of her has her wanting to possess Erich.

Mely: I would like to say something about the surprise reveal that Oskar's father murdered his mother, but I just do not know what to say.

Oyce: I love how Gustaf/Gustav--wtf proofreaders--is going half blind due to murdering his wife. Oh, manga.

Mely: I was so convinced for most of the book that it was suicide. It even happens several days before Christmas!

Oyce: We don't even get a big panel for the shocking reveal.

Mely: But Oskar apparently still misses his father like crazy and doesn't blame him. His dilemma is not that his father killed his mother, but that he doesn't know how to deal with his bio dad.

Oyce: I think I read Oskar's longing for his stepfather more as a longing for a father figure in general.

Mely: What do you make of Erich's relationship with his stepfather at the end?

Oyce: I actually liked it, although I am annoyed Hagio had to kill off Marie to get to that point. Heterosexuality: don't engage in it, girls, it only ends with your death! That is probably too cynical. There are Juli's mother and Thomas', but they aren't really shown in romantic relationships.

Mely: Yes. You can reach emotional and sexual maturity and develop healthy bonds with a father figure -- but only if your mother dies! This appears to be the case for Oskar, too.

Oyce: I love that Erich and Oskar canonically bond over both having two fathers. Surfeits of fathers and dead mothers everywhere!

Mely: Except for Juli! Who has no father figures but both a mother and a grandmother.

Oyce: I wish I knew how Marie compares to previous shoujo mother figures. From what I’ve read, a lot of early shoujo featured preteen girls being separated from their birth mothers or being abused by evil stepmothers.

Here we have Erich tragically separated from his birth mother, but Marie is a very glamorous but also childlike figure, rather than being typically maternal. And of course, there’s no reunion for Erich.

Mely: There are an awful lot of childlike mothers. Juli's mother is relatively kind, but Juli is clearly the caretaker of the family -- his mother is not a resource for him. His grandmother is a harpy. Thomas' mother is completely broken down -- understandably, but we literally never see her outside her home, whereas her husband can function.

Oyce: Then there’s Juli's evil grandmother and her racist rants about Juli’s dark-haired Greek-German father and the similarly dark-haired Juli. Juli’s sister, of course, is exempt because she has the beautiful blonde hair and blue eyes of a true German.

Mely: We should probably talk about otherness and the racist rants. It's not really about race, here, I think? It's just another way to emphasize Juli's otherness. And--ugh--perhaps his sense of dirtiness? Innate defilement?

Oyce: Ugh, yes. It felt like a very romance-novel treatment of race to me, where the dark swarthy people are Italian or Spanish or Greek. And it's also very romance-novel-esque in how political issues such as race or abuse are treated largely in how they personally impact the protagonist, and less in an institutionally oppressive context. But that is also me bringing my own context in.

Mely: No, I think that makes sense. The racial subtexts here are so clearly filtered through American and European media. Which doesn't make them less politically horrible, but which does make them less emotionally horrible to me, if that makes sense? It's so clearly unrelated to any real world context for Hagio.

Oyce: It also helps for me that it's set in such a fantasy setting. And that it was written in the 70s. And just how everything is kind of symbolic and personal and deeply psychological with Hagio.

Mely: Can we talk a bit about Thomas' suicide?

Oyce: I had so many issues with that! Probably even more than the treatment of abuse. I was just horrified by how it was clearly supposed to be something romantic and touching in the text, when all I could think of was how this young boy was laying the responsibility of his entire emotional state on Juli. The age also horrifies me.

I also hate how it supports the all-too-common trope that if one person has an overwhelming crush on another person, the other person should return it. And I feel this is present in manga of all sorts as well as Western media.

Mely: Thomas is treated more like a woman than any other male in the narrative, by which I mean he's a symbol rather than a character. We don't actually get a reason for his suicide beyond "The person I love has rejected me!" which ... is not a reason for suicide outside romantic dramas.

Oyce: Exactly. And Hagio manages to make it not quite as terrible as I had expected by making it more about Juli's inability to accept love, but by "not quite as terrible" I mean "Did not throw my extremely expensive edition across a room or immediately stop reading." It is incredibly abusive and manipulative, and it was actually a bit triggery for me. Hagio does put a different spin on it by implying that Thomas kills himself as a way to rescue Juli rather than out of unrequited love, which lessens the cultural narrative of forcing someone to return your emotions. Then again, while it’s nice to want to help someone heal, suicide, I think, is really not the best method.

Mely: Thomas' emotional blackmail is related to the way Oskar initially attempts to force Juli into an emotional confrontation, I think. It's this cultural trope that you can force withdrawn or repressed people to heal that I see in both manga and Western culture.

And on the one hand, in the narrative, this clearly makes things worse for Juli for a while, as it pushes him even further away from honesty and emotional engagement with his friends, and on the other hand, it all turns okay in the end! Which. Um.

Oyce: Yes, it’s not a trope I’m particularly fond of. There’s also the overall romantic fascination with death and violence--Erich’s first bout of strangling himself occurs after he sees Marie and her lover.

Mely: I think the German background here is very significant, and probably related to Goethe's "The Sorrows of Young Werther."

Oyce: Oh, tell me more! I don't know about this.

Mely: I am very sure Hagio was aware of the novella, given the dissemination of European classics in Japan.

Oyce: And Thomas' last name of "Werner."

Mely: Right. "The Sorrows of Young Werther" is a semiautobiographical novel about the unhappy love of a young Werther for an engaged and later married woman, who eventually returns his love but refuses to act on it. When she tells him she can no longer speak to him, he kills himself. It's a foundational work in the German Sturm und Drang school, which greatly influenced the English Romantics. Palely loitering, tragic loves, romantic suicides, suicide pacts.

This made Goethe a literary rock star across Europe in the late 18th century. It also inspired a rash of copycat capital-R Romantic suicides.

Oyce: Ha, yes. That actually reminds me of how certain kabuki and bunraku plays were banned in Japan due to the same subsequent copycat suicides. Though those were more often double suicides instead of one lonely lover.

That said, I'm glad Hagio has most of her characters choosing life in the end.

Mely: It is interesting that Hagio's twist on this wasn't ultimately another romantic suicide, it was a gesture towards life and healing. Which does make me react more positively towards the ending.

Oyce: Yes, me too. And I think in the end, even though the text sees it as a romantic gesture, Oskar and Juli and Erich all reject the idea of taking your life. I'm particularly glad that it's how she begins the story, not how she ends it. That made a big difference to me – she's engaging with the “tragic lover” trope and subverting it instead of adopting it wholesale.

Mely: To be shallow for a moment: I shipped Juli/Oskar way more than Juli/Erich.

Oyce: Oh man, I totally shipped Juli/Oskar more! I didn't actually like Erich that much.

Mely: I didn't like Erich, either! And now I am trying to think why? Because I also felt bad for him and kept yelling Gift-of-Fear advice. Get away from the roommate who threatens to kill you, Erich! I realize your schoolmaster is setting you up, but run!

Oyce: Ha, yes. Erich is so much more a plot device than I had expected. I mean, I sympathize with his feelings about being a substitute for Thomas, but he's more a catalyst for Juli than a serious romantic interest.

Mely: Right. And then his family relationships also become an examination of trauma and healing, as do Oskar's. It feels more successful in terms of theme than in terms of plot -- I could see the point, but I kept wanting to get back to Juli.

Oyce: I actually liked Erich best when he wasn't loving Juli. Because then he was much more his own character, as opposed to being a means for Juli to forgive himself. Oskar, though... I really liked Oskar!

Mely: I loved Oskar! Actually, in the beginning I thought he was an awful friend: Why are you pressuring your friend to emotional disclosures he is clearly in no place to make, Oskar? But by the end I had a much better sense of him.

Oyce: I think I was surprised by how much I liked Oskar and how central he was to the story. And I feel like he's the prototype for so many of the extremely charming third-wheel characters I see in some manga, for example, Asaba, Arima and Miyazawa's dandy friend in KareKano, and Nakatsu, the guy who also falls for the heroine in HanaKimi. Part of it is the personality template -- the frivolous playboy with a deeper side. And some of it is definitely the role they play in the story.

Mely: That is interesting. I like Oskar so much better than either of those guys! I think partly is related to shift in focus, which results from the move to more typical shoujo plotlines and possibly heterosexual romance? Heart of Thomas is very much Juli's story, with everything else supporting that. In the het romances, the Erich character becomes the female lead and Juli becomes the male lead.

Oh, so that's why the male lead's MANPAIN always takes over the narrative at the end. We can blame Thomas.

Also sexism.

Oyce: Argh, sexism!

I think the Oskar role is much more interesting when the story isn’t as heteronormative as most shoujo plots. Otherwise, he’s either a distraction to the main plot that is the hero and the heroine getting together, or he becomes the person you secretly root for. In both cases, it’s a role that is limited by the romance.

Mely: But it does underline what you said before, how Thomas is ultimately much less of a romance than it initially seems.

Oyce: Yeah. What drew you to Oskar so much?

Mely: I am trying to figure out why I like him so much.

I do love his introduction, that first panel, which is still in the color section, and the pink that has before been used for emphasis and human skin just takes over the entire panel. But we first meet Oskar sittting on a windowsill, looking down at Juli running -- or rather, that's the second panel we see him in, the one that tells us exactly what we're looking at; the first one is a close-up on his mouth, a cigarette, the whirls of smoke. And it's so pink! So pink and sensual.

And cigarettes will later be important.

So one thing I like about him, from the very beginning, is this sensuality, this sense of comfort and pleasure in the body. He's in a bathrobe, his body language is relaxed (later even floppy), he owns his own space.

It's a big contrast to Juli, so tightly wound, so literally buttoned up.

Oyce: Yes, I love that Oskar's so insouciant. And he has the floppy bangs as well.

Mely: I get the sense very early that Oskar is by far the person in Heart of Thomas who is the most comfortable with himself, emotionally, physically, and sexually. I also take his name as a reference to Oscar Wilde. Who was famously not pretty, unlike Thomas' Oskar, but who was also famously witty and famously gay.

But yes -- we see Thomas in the cold, so much snow and so much solitude, and then Juli in a crowd but just as solitary and just as cold, and then suddenly there's Oskar in a bathrobe, smoking a cigarette.

Obviously cigarette smoking -- especially underage cigarette smoking -- was more common in both real life and in narratives in 1971 than it is now. But I don't feel like I'm overreaching when I read a connection between Oskar's carelessly draped cigarette and the cliche of the post-coital cigarette. I do think it's one of the things that primes us to read Oskar as a sexual being, and a person comfortable with his sexuality, in a way that the other characters aren't. And in Heart of Thomas there's a strong correlation between being comfortable with your sexuality and being comfortable with your emotions.

By "sexuality" here I'm not sure how much I mean "homosexuality" as opposed to "having sexual desires". Because in Heart of Thomas it almost seems like all sexuality is homosexuality. It's the default.

Oyce: Although I find it interesting that even Oskar, who is most at ease with his own sexuality, also isn't really portrayed in a sexual relationship. I feel like Oskar is almost the line between comfort with your own sexuality and actually having sex, a la Siegfried. Er, at least I assume Siegfried is either having sex or partaking in BDSM or something. And even with that, the physicality isn't very overt. There are the few CPR kisses, and with Siegfried and Juli, the emotional and mental impact is far more important than what happens physically. There’s nothing like the infamous bed scene of Takemiya Keiko's Song of the Wind and Trees.

To add to your cigarette theme, Oskar and Erich are talking about why Erich dislikes kissing and Oskar offers him a smoke. Erich declines, saying he hates cigarettes.

Mely: I had forgotten that!

We get so much emphasis on Erich's childishness. Oskar's nickname for him is even "Le Bébé" (the Baby). In one scene, Erich is asleep in bed that looks like a crib, with baby Erich seen through the bed/crib bars, and Oskar, sitting in a chair next to him, appears to be twice his size.

Oyce: And in one of the few mentions of heterosexuality with the students (as opposed to the parents), Oskar says he will cure Erich of his fits by taking him out on a "girl hunt."

Mely: Is that when the town girls giggle and Erich blushes? Erich's fits will be cured by adult sexuality! So very Freudian.

Oyce: Yes, that's when. I think that's when he first sees Siegfried, too. And more on the romantic vs. sexual, Erich first begins strangling himself not just when he sees Marie kissing someone, but when they are kissing, half lying down on the sofa, with pretty clear sexual overtones.

Mely: To get back to the cigarettes: Oskar smoking is a comparison and contrast to Siegfried with a cigarette. Oskar doesn't burn his lovers with cigarette stubs, but the only time we see him actually engaging in sexual behavior is when he kisses Ante, which is very Harlequin savage sheikh -- Ante provokes the kiss! The kiss is violent! The kiss is contemptuous!

And in a larger cultural context, the association of homosexuality with contempt and violence is troubling, but I think what Hagio does by making this world all-masculine is say not that homosexuality is scary and violent and overwhelming, but that all sexuality is scary and violent and overwhelming -- because this is the only sexuality we see.

Oyce: Yes, especially because historically speaking it's also very possible that for the readers of the time, it's one of the first scenes including sexuality they are seeing in the pages of manga. Which ... obviously not all of us are reading it in that context any more.

Mely: And obviously this is sex-negative in some ways, but I feel like it is also a magnificent expression of how scary sex can be for adolescents. I think my favorite example of this is the scene where Juli has a nightmare of thomas dissolving into a cascade of flowers and jolts awake crying THOMAS! I read this as both nightmare and wet dream: Thomas' treatment of sexuality in a nutshell.

Oyce: But I also think the remove of the setting and the time period, which feels deliberately vague, as opposed to say, Urasawa setting Monster in Germany, contributes to reading the sexuality as a symbol instead of a critique of homosexuality.

I don't know if Hagio had the same associations with boys' schools that we do, or that maybe Westerners did in the past, but I suspect she did? I mean, Mishima Yukio’s Confessions of a Mask, which is about the author’s growing realization of his own homosexuality set in a boys’ school, was published in 1949.

Mely: I do think the all-male world makes it much easier for Hagio to talk about sex.

Oyce: Definitely. I think that's why Takemiya and Hagio turn to BL.

Mely: As mentioned previously, Hagio tried to make it a girls' school originally but gave it up because it was silly. Thorn's intro explains,

But it didn't work with a female cast. Creating as a woman, for female readers, she found herself wanting to make every action more realistic and plausible. As she put it in her 2005 Comics Journal interview, "It came out sort of giggly."

Not sure what to make of that.

Oyce: Urgh, I have so many issues with the idea of girls' sexuality as gross or weird or silly, but then again, I am not from that generation. So ... YMMV.

I also keep remembering a BL writer's quote about girls' kisses being sticky like natto.

I don't want to condemn, especially given how Thomas is in many ways the first of its kind. But I do have issues.

Mely: Yeah, my feelings about BL -- about the exploration of female sexuality, the appropriation of gay sexuality (if the writers or readers are straight) and the use of male characters to explore female sexuality -- are extremely conflicted.

Can we talk about the humor?

Oyce: I ... don't actually remember any of the humor? Except possibly the teasing and the schoolboy talk with Ante, which really don't work for me.

Mely: There are various bits of humor associated with the underclassman and meals and getting into food fights. I wanted it all to go away so I could focus on the DRAMA.

Oyce: Oh, yes! I generally ignored or skimmed any of the scenes in the school that didn't have to do with the DRAMA. I wonder how much of that is in part due to Thomas being the first work in a genre. I feel like I get those moments that really yank me out of the text in Rose of Versailles as well.

Mely: I don't know if it's the first work thing. A lot of manga has a humor/drama balance that doesn't make sense to me.

Oyce: The chibi-fication factor? I know some people first getting into manga and anime have said it weirds them out.

Mely: Maybe. I mean, I got used to that, but it was enormously disorienting at first.

Oyce: How does the humor/drama divide work for you in Thomas as opposed to other works of manga? I did notice it more for Thomas than I do for a lot of modern manga, but I can't put my finger on why.

Mely: It's mostly entirely separate characters. Like grave diggers in Hamlet. Rustic clownes.

Oyce: Like the many school boys. I think one of the reasons they annoy me is because Juli and Thomas and Erich and Oskar and Siegfried really don't act like schoolboys, particularly not schoolboys of their age. Whereas the anonymous boys are much more like regular schoolsboys, and it's very jarring compared to the psychological depth of the others. It takes you away from Hagio's imagined Occident and into something that is closer to the actual world, at least for me, and destroys a bit of my suspension of disbelief.

Mely: Oh, you know, the character besides Oskar who seems reasonably comfortable with himself and emotionally intelligent, is the big fat guy with the extravagant waistcoats, who looks much more like Oscar Wilde than Oskar does. He, too, seems to have wandered in from the alternate universe where Heart of Thomas is a comedy.

Oyce: We should talk about the paneling. I remember reading Matt Thorn about shoujo paneling, particularly the innovativeness of the full-page spreads with abstract figures meant to portray the characters’ psyches, and in comparison, I didn’t think Thomas' paneling was that exceptional. But now that I’m flipping through it again, there really are many more big spreads than I had remembered. And not only big spreads, but big spreads with very symbolic elements, like the starry backgrounds or various collaged faces.

Mely: See, what really struck me is how crowded everything is. There are almost no full-page spreads after the opening pages. Even Thomas' suicide and Juli's breakdowns don't get a full page. They get maybe three-quarters of a page. There's this kind of density to it, in that Hagio is trying to cram in SO MUCH, but also trying to elongate these moments of emotional intensity. And I haven't seen Hagio's recent work except for what's come out in English, but I think contemporary shoujo or BL would give the climactic moments full pages, or even two-page spreads.

Oyce: Yes. Well, and I remember from the introduction that she only thought she was going to get an issue, and she kept stretching it out and hoping her editor wouldn't pull it.

Mely: Yes! It's kind of hilarious. She would keep promising that she was going to wrap things up and then she would just write whatever she wanted anyway.

Oyce: Yes! I love it. I am SO HAPPY it didn't get pulled. But I think it really must have affected the pacing.

I can see what you mean by how crowded it is. It didn't quite seem that way to me, given how large the Fantagraphics volume is, but there are a lot of panels per page.

Mely: It's hard for me to imagine how they print it in the smaller size. How is the text legible?

Oyce: I have no idea. I was thinking it'd be hard enough to read in tankobon size, much less bunkobon, which is even smaller. I wonder how big the manga magazines at the time were. I wish I had read more stuff from this period to know what the paneling and page layout norms were.

Mely: Yeah, I've seen excerpts of predecessor shoujo in books and exhibitions, but I think there's nothing available in the English earlier than this, Takemiya, and Tezuka.

I was thinking about paper scarcity, and that the crowdedness might be due to not having much page count. Although that was probably just a post-WWII problem. But maybe there's still some aesthetic influence?

Oyce: Right. Also, a lot of manga pre-Tezuka were 4-koma newspaper strips. But again, I don't know how prevalent 4-koma stripes were when Hagio was creating her work. I haven't read enough early Tezuka to know how it looks.

Mely: I saw Princess Knight panels in an exhibit and the originals were so small. The penpoints or brushes must have been tiny! The control was amazing.

Oyce: Yes!

Mely: You mentioned the collages before. I like the way things melt into each other, faces, backgrounds, obviously meaning what people are thinking of, but also making it feel like the borders of identity are porous, there's a flow from person to person, person to environment. I like it in shoujo in general, and I like it here.

I do feel like Hagio has a great delicacy of line, even compared to modern shoujo. There are some mangaka with wispy thin-lined styles, but Hagio and Takemiya both seem to have finer lines and much more intricate shapes. They really like curls, curlicues. It's so girly! I love it.

Oyce: Yes, me too! I especially love how detailed it is compared to a lot of modern shoujo, which sometimes feels more deliberately pared down.

And I usually don't like older shoujo art that much, but I was struck by how easy it was to read Thomas. For example, I remember having difficulty with Rose of Versailles art. I love the character design. I thought I'd have a difficult time telling Erich and Thomas apart, given the premise, but I really didn't.

Mely: I attribute it to the hair. Erich has curly hair. And also facial expressions besides sad devotion.

Oyce: I attribute it more to the facial expressions! Since Yuki Kaori also has characters with different hair, and I cannot for the life of me tell them apart sometimes. Probably because they all look caught between love and hate.

But yes, I love how the differences in expression with Erich and Thomas is also indicative of how Erich manages to "succeed" with Juli in ways Thomas doesn't, à la the Manga Bookshelf discussion.

Mely: Erich also needs Juli's help in ways Thomas doesn't seem to, i.e., Juli finding him when he runs away after learning of his mother's death. Getting to be his rescuer as a step away from the possibilities offered by Siegfried, either victim or victimizer.

Although, if I recall correctly, Juli's threats to kill Erich come after that, so maybe not so much.

Oyce: I found the death threats so disturbing! I suppose you can read them as Juli nihilistically taking on Siegfried's point of view for himself, but still.

Mely: For most of the book Juli seems on the verge of flying apart into some terrible violence. Mostly it seems self-directed -- the shocked reaction when Oskar sees his burns -- but he turns it on Erich pretty easily.

Oyce: Yes.

About the art: I do think the androgynous beautiful boys in so much of shoujo are due to Hagio and Takemiya, but alas have no proof of this.

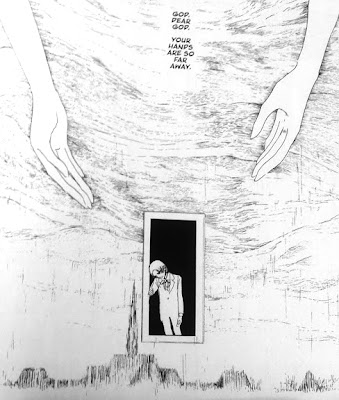

Mely: I love the three-quarter page image of Juli leaning despairing against a black doorway, over a vague cityscape: "God. Dear God. Your hands are so far away." Moto Hagio does the BEST melodrama.

Oyce: I KNOW.

In conclusion: we have no conclusion, and it’s taken us so long to think of one that we haven’t posted this for months and months. So ... read Heart of Thomas and discuss it with us!

no subject

Date: 2013-05-29 09:58 pm (UTC)^.~